I think it’s enough for us to know that it was pulled off by American special forces and, as I wrote the other day, that it was completed in accordance with the law and the rules of engagement for the mission. That’s it.

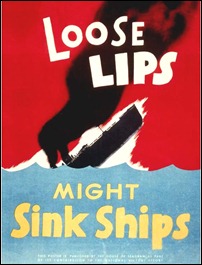

We don’t need to know what unit flew the helicopters, we don’t need to know from where they launched their mission, we don’t need to know how many flying back-up helicopters they had, we don’t need to know what kind of covering air support they had, we don’t need to know about the extent to which electronic interdiction was employed in the area. We don’t need to know any of that. It was a secret military operation and it needs to stay classified that way until the either the tactics or the enemy become obsolete.

Little bits of information, including the kinds of aircraft we used and the fact that weather forced a postponement the night before can provide insight on origins, routes, and go/no-go launch and execution criteria.

We shouldn’t discuss our intelligence-gathering, our safe houses in the area, our reconnaissance, surveillance, and intelligence assets in the area, our considerations and concerns, and I’m not even crazy about publishing the rules of engagement (ROE) for the mission.

When we publicly announce what we will and won’t do operationally, we hand the enemy a huge gift. When we say, for instance, that we won’t target enemy elements in populated areas, we immediately find that our enemy moves right into those areas. They start setting up anti-aircraft batteries and mortars at mosques and shrines and in neighborhoods. We have to be careful with even the most innocuous-sounding information because it can be pieced together and molded into real insight.

Just as we were able to piece together bin Laden’s whereabouts from interrogation products gleaned from prisoners, including the nickname of one of his couriers, we should realize our enemy can learn a lot about our intuition and thought process from that information. In a lot of ways, we’re better off when our enemy doesn’t think we’re so clever.

Personally, I see a lot of benefit in not saying anything at all about bin Laden’s killing, not even to say it happened. Let’s let the incident simmer and let it froth up a bit. When we’re asked about it at a press conference in a couple of weeks, we can say, “Yeah, we killed him. We said we were going to, didn’t we?” Next question.